|

Dear Friends,

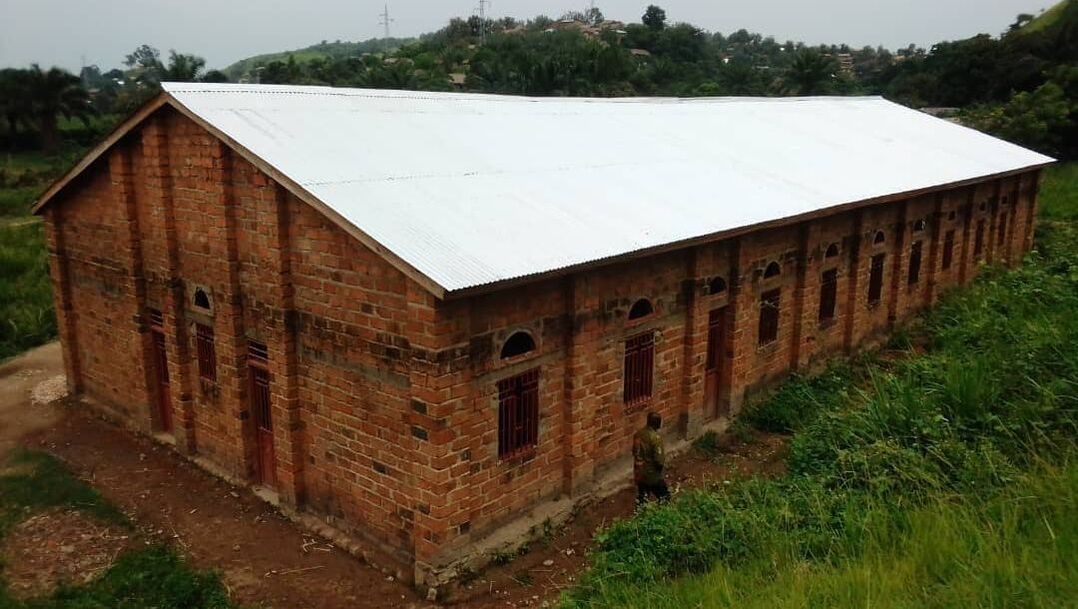

2019 was fruitful year for FPM as even more dreams became realities. Below are some of things we accomplished thanks to your support. Friendship-Building Tours FPM sponsored two friendship tours in 2019. On the Indiana tour, Pastors Lana, Joseph, Mumba, and Jackie as well as Papa Londwa traveled around the state visiting old friends, making new friends, and sharing with folks about the ministries of church leaders in the Tanganyika Conference and the challenges they face. (for more about this click here ) The second tour was a joint educational friendship-focused program of FPM and Purdue University’s Wesley Foundation. On this tour, young adults from the USA, Africa University students and graduates, as well as FPM leaders in Congo went on an epic road trip together. The voyage began at The UMC’s Africa U. in Zimbabwe, then down by bus to Victoria Falls, up by public busses through Zambia up to The UMC’s Mulungwishi University in Congo, and finally all the way up to Kamina by bicycle (more on their itinerary here). In addition to building new friendships, the tour functioned as a traveling missiology classroom. Participants read Biking Bob’s book (including excerpts from the not-yet-published sequel) and had challenging conversations about healthy ways to build friendships that cross socio-economic and cultural boundaries. One participant’s reflections can be found here. Spreading Missiological Education Taylor completed her DTh in Missiology, and her thesis, Decolonizing Mission Partnerships was selected by the American Society of Missiology to be published in its monograph series. The book is scheduled to come out in late 2020 and will become one of the core textbooks for FPM’s curriculum. As FPM’s lead coach, Taylor gave a number of keynotes, workshops, papers, and university guest lectures on the topic on rethinking understandings of mission as well as exploring and addressing the impact of racism on us all. Her teaching ministry took her to events on three continents. In addition, she taught the spring Course of Study on Mission at Wesley Theological Seminary, using a curriculum she has been developing for FPM. Grants, Scholarships, and Construction Support FPM continues to help connect important ministries in North Katanga and Tanganyika with folks with the financial means to support them. Some of the programs your contributions supported in 2019 were:

2020 is looking to be another great year. Our core leadership team has expanded and is more active than ever before, and together we are dreaming and discerning where the Spirit is leading us next.

1 Comment

L - R: Succeed, Elizabeth, Simbarashe L - R: Succeed, Elizabeth, Simbarashe Originally published in the Fall 2019 newsletter of the Baptist Student Foundation at Purdue University. This trip involved traveling by bus and bicycle through Zimbabwe, Zambia, and into the Katanga region of DR Congo. By Elizabeth Marie Sowinski The Zulu word “Ubuntu” is used to describe the interconnectedness of mankind. It roughly translates “I am because we are.” Among many devoted Methodists whom we encountered in Africa, ubuntu is a way of life. They live and breathe to serve their communities, prioritizing them second only to their Creator. We can learn much from people like these, but I would like to emphasize three lessons. First, Westerners can learn a lot from their attitude toward trials in life. In my short month in Africa, we encountered countless challenges to our mission. They ranged from minor irritations to major obstacles. Despite all these troubles, a way always presented itself. Call it faith, endurance, or divine intervention; things always worked out in one way or another. In this, we had to learn to trust in our African friends, leaders, and our God. Often, if not most of the time, our situation was out of our hands. We regularly encountered times where there was nothing that we as American students could do to fix our problems. We simply had to trust in the people that guided us and the God we serve. This led to countless changes in our plans and moments of anxiety as we had to entrust our cash, passports, or even our safety into the hands of a “friend of a friend,” whom we had only just met. Nevertheless, they always maintained their integrity and made sure that we were safely delivered to the next step of our journey. Despite their poverty, our brothers and sisters always made sure that our needs were provided for. Their outpouring of generosity was humbling. The churches that we visited have very little money and few resources, but we were never in want. Their hospitality and kindness are truly astounding. The second lesson that we can learn from our African brothers and sisters is that home is people. Home is not a place. Home is not an object. Home is not a feeling. Home is people. People who accept you, love you, and want you. This is how I traveled many kilometers across a foreign land without leaving home even once. As we journeyed from place to place, we met many new people. Often, we would only had the opportunity to spend a day or two with them. Nevertheless, we were welcomed with open hearts and open arms, as a long-lost family member coming home. In a way, we were family, united under the Methodist cross and flames and, ultimately, under our Father and Savior. In each new location, we entered a communion with our brothers and sisters in Christ that truly made it our home. The final lesson is by far the most frustrating, but also may be the most important. Most Christian leaders that we met on this trip are passionate, driven, and willing to do whatever it takes to save their communities. Furthermore, these people are already in place to make a difference as leaders in the church, local government, or even simply among their peers. As Westerners, we may have passion and an intense desire to “save” the innocent from the affliction that is poverty. To rescue children from hunger and disease. To end the suffering that comes from destitution. However, it is vital that we recognize that we quite literally cannot. We are not capable of fixing these problems for our friends. Westerners made this mess decades ago, and corrupt governments perpetuate it, but we Christians and servants on this side of the world do not have the ability to liberate our brothers and sisters from their trials, no matter how much we try. Rather, to truly help, we must humble ourselves, deny our hero complex that dominates so much of traditional missiology, and instead pour our efforts into supporting those who can make a difference in their own communities. In this way, and this way alone, can we help bring about deep systemic change. As much as we would like to step in and “fix” the situation, we are simply too far removed from the source of the problem. We are not in a proper place to affect lasting change, and any attempts to muscle in and do so will ultimately fail, if not cause even greater damage. There are several great dangers in that approach. First, it establishes a system based in patronage that creates a dependency on wealthy Westerners. It handicaps local leadership by implicitly attempting to convince them that their efforts are not enough, that they cannot make a difference by themselves, and that they require the generosity of a rich white person to do effective work. That is a toxic mindset and can be extremely damaging in the long term. It is also the greatest downfall of traditional missiology. Second, when Westerners try to resolve uniquely African complications on their own, they inevitably impose their own Western culture on the victims of their “aid.” African culture is already rich, deep, and plentiful. They do not need our ideology trampling on their way of life. This can lead to several societal complications, including a chance of instilling into Africans the idea that they should attempt to mimic Western doctrine. Western culture does not necessarily mesh well into African culture, and while both are valid and important, Western dogma will not resolve African problems. So then, what can we do to help our Christian brothers and sisters who suffer in poverty? The answer is that we support them as they resolve their own situation. This can manifest in many ways, and it can be difficult to distinguish between supporting local leadership and endorsing patronage. Further, it is challenging to relinquish control and trust our African friends and colleagues to develop their own ideas and use their own methods, despite their lack of resources. Personally, I feel a sense of helplessness when I am unable to bring aid to a loved one. This tempts me to feel hopeless about their destitute condition. However, this I know: the need is great, but the passion and devotion of many Christian leaders is greater. These people are in place to help; we are not. They are in a position where they can do far more good than we could even hope to accomplish. Western culture emphasizes individualism and independence. Because of this, we often feel the need to fix things on our own. We will assist another person because of our own desire to feel good about ourselves. Looking deeper, you can see that this is rooted in a sense of pride, intertwined with hopes of heroism and moral superiority. This is not servanthood. In order to see widespread, systemic change, we must lay aside our ego, humble ourselves, shut up, and listen. Stop the advice, stop the missions, stop imposing, and listen. The people of Africa have spent their entire lives dealing with the crises that we have only just begun to see. They know the inside, outside, upside, and downside of their situations, and only they know what needs to be done. If we can lower ourselves and uplift the locals, if we can support their ideas and projects, and if we finally acknowledge that we are not the heroes but rather a part of a team and family, I believe that together, the body of Christ will be unstoppable in our calling to love and serve one another in unity, hope, and peace. TO TRULY HELP, WE MUST HUMBLE OURSELVES, DENY OUR HERO COMPLEX THAT DOMINATES SO MUCH OF TRADITIONAL MISSIOLOGY, AND INSTEAD POUR OUR EFFORTS INTO SUPPORTING THOSE WHO CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE IN THEIR OWN COMMUNITIES. |

- HOME

- ABOUT US

- OUR BOOKS

-

OUR WORK

-

HISTORY

>

- 2023 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2022 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2021 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2020 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2019 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2018 YEAR IN REVIEW

- 2017 Year in Review

- 2016 Year in Review

- 2015 Year in Review

- 2014 Year in Review

- 2013 Year in Review

- 2012 Year in Review >

- 2011 Year in Review >

- 2010 Year in Review >

- 2009 Year in Review

- NURSING SCHOOL

- WOMEN'S FOYER

-

HISTORY

>

- DONATE

- BLOG

- CONTACT US

RSS Feed

RSS Feed